A patent from that year documents as much.

As to the drink's specious name—well, like much of history, you must take most of the story on faith.

The legend holds that Morrison named the soft drink after a former employer, Dr. Charles Pepper, of Rural Retreat, Virginia.

Pepper had been a surgeon in the Confederate army before retiring to open a pharmacy in Rural Retreat, from which he dispensed a sweet and spicy elixir not dissimilar to Morrison's later concoction.

The legend suggests further that Morrison was Dr. Pepper's assistant and was in love with the doctor-turned-pharmacist's daughter.

Told he wasn't suited to marry the boss's daughter, Morrison swiped one of the doctor's formulas and fled to Texas.

But whether Morrison ever worked for Pepper is questionable.

Although US Census records show Morrison indeed lived in the vicinity of Rural Retreat and worked as a pharmacy clerk, he may never have even known the doctor, much less worked for him.

But Morrison, aiming to turn his soft drink into a powerhouse throughout the South, was happy to market it under Pepper's name and title.

By doing so, he reasoned, he could conjure both the notion of "healing" and warm memories of the Lost Cause—a winning combination in the soul-sick South.Morrison's branding strategy worked.By the turn of the 20th century, his company, Artesian Manufacturing & Bottling, had sold hundreds of thousands of bottles of Dr. Pepper in Texas and Virginia.

Even today, ignoring "woke mobs," the company stands by the legend that Wade Morrison named Dr. Pepper after the Confederate surgeon.

POSTSCRIPT: To learn more about Dr. Pepper's brand history, go here.

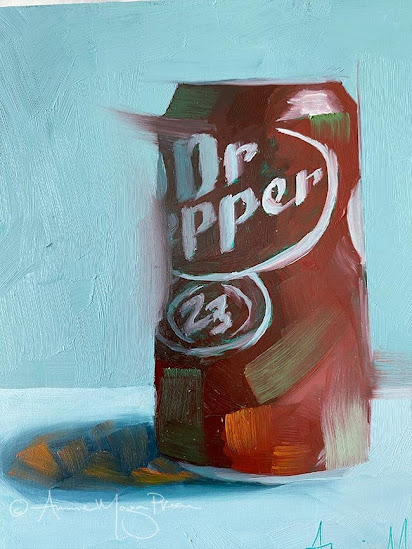

Above: Dr. Pepper by Annie Morgan Preece. Oil on canvas. 6 x 6 inches.